2019

2019 in review

The Global Change and Tropical Conservation lab at HKU has been busy in 2019. The below is a reflection on the year and on some the research published during this dynamic year.

This year has been a very difficult one in Hong Kong. Half of 2019 has seen large protests all across the city. In November, HKU was shut down for a week as protestors took over the campus and fortified it in anticipation of police entering by force (an event which fortunately did not take place). The semester was also cut short and moved online at that time.

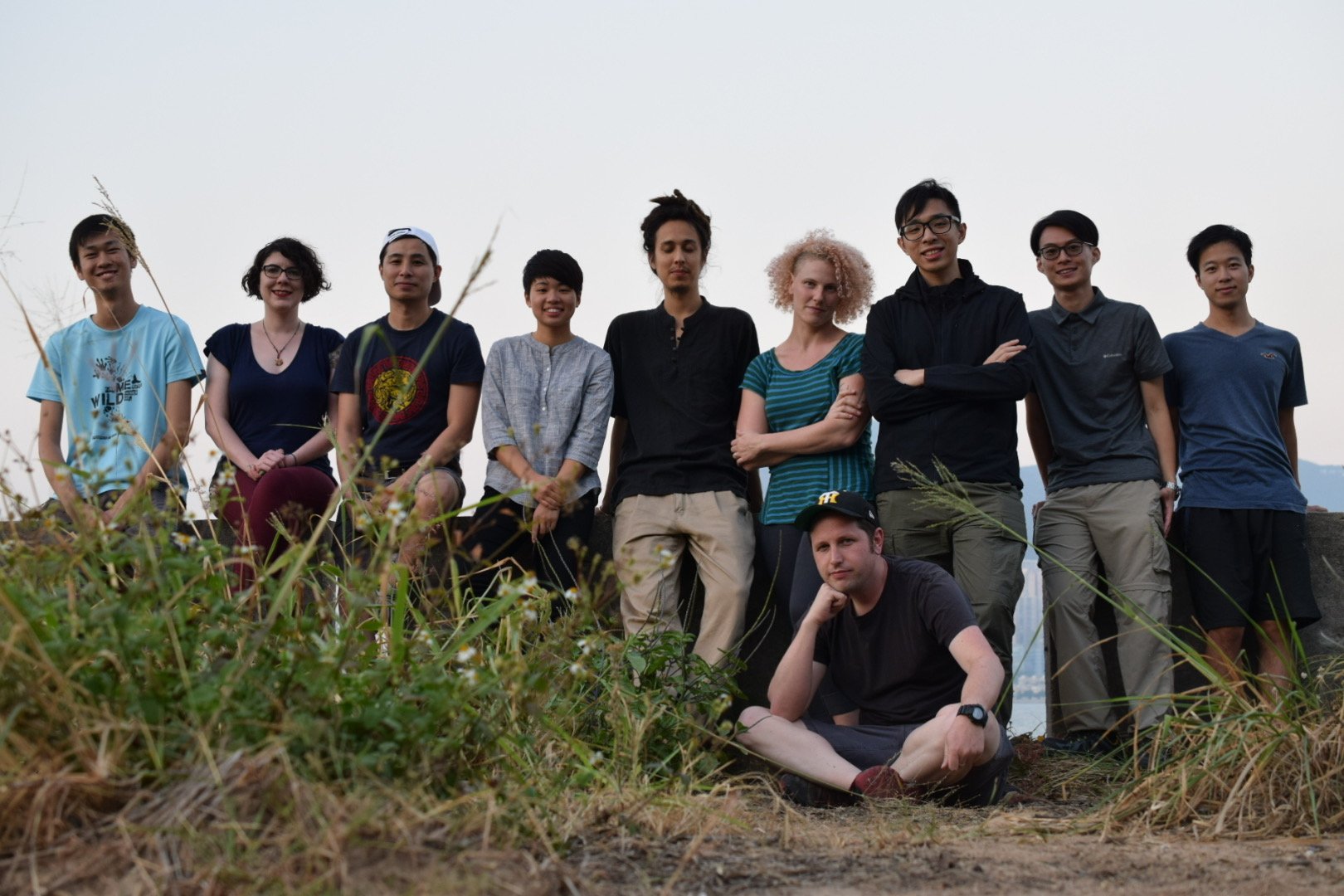

But the lab kept moving and we continue to science! There was considerable turnover in the group: Shuang Xing, Sam Yue, Calvin Leung, and Melanie Chan all moved on to bigger and better things while Yuet Fung Ling, Wing Sing Chan, and Huai-Hsuan May Huang all joined as new members. Tim took on a position as the Acting Director of the Ecology & Biodiversity Research Division. Postgraduates did extensive field work for much of the year; Pauline in South Africa and Hong Kong, Felix in Japan, Michel in Cameroon, and Anna and Sharne in Hong Kong. And everyone continued in various analysis and modelling endeavours in the lab. Here are some example of papers that came out of the lab this year:

Managing multiple threats to biodiversity and IPBES

When I started my PhD (15 years ago!) I had very little interest in the topic of climate change. It just didn't seem that important to me in light of other more pressing threats to tropical species like habitat loss. But as I studied the topic more and more I realized that this wasn't really a realistic view of the issue. In late 2017 I began writing a perspective piece that was a consequence of a revisiting this issue with Freda Guo (at the time an MPhil student), David Baker, and Caroline Dingle. Essentially we were arguing for a more holistic view of threats to biodiversity and the importance of tackling all of them at once rather than focusing on individual threats, potentially to the detriment to the species or ecosystem in question.

We wrote a draft but had a lot of trouble finishing it off. There was a lack of coherence to the argument and some of the finer details. Then, during happy hour following a departmental seminar one evening, Louise Ashton and I were discussing the multiple threats issue. As it turns out, she and Roger Kitching were writing a similar perspective piece. We combined forces! The complementarity in our ideas strengthened the perspective and allowed us to complete the manuscript in good time. Less than a month after the paper was published in TREE the IPBES Global Assessment was released. Following a response to our paper by Nicolas Titeux et al., we were able to discuss our suggestions for integration of proximate and horizon threats to biodiversity in the context of the IPBES assessment.

See paper in Trends in Ecology and Evolution as well as follow up Letter

So how do we evaluate multiple threats for an iconic and data-deficient butterfly?

I first went to Vietnam in 2011 and was very fortunate to meet Vu Van Lien in Sapa on that trip. We discussed a variety of issues but one fascinating topic was that of Teinpalpus aureus. He explained that there was very high demand for the species and that a lot of collecting was taking place for the international market. Over the next several years in Hong Kong I would return to the species every once in a while and consider possibilities for conservation.

But it wasn't until 2016-17, with support from an HKU Seed Grant, that Tom Au and Shuang Xing stepped up to do some real work. Tom travelled all across China and Vietnam to collect distribution records of the species, which were scattered and not readily available. Pauline Dufour and Shuang also began monitoring online trade in the species. Tom, Wenda Cheng and Felix Landry Yuan then constructed species distribution models to evaluate climate change and habitat loss threats to the species. Finally, Shuang coordinated all of the individual pieces to lead the writing of the manuscript which showed how all of these threats together (habitat loss, climate change, and wildlife trade) threatened the persistence of this iconic species.

See paper in Biological Conservation

What can local ecological knowledge tell us about rare Hong Kong otters?

When Sharne began studying Hong Kong otters with Billy Hau and myself (with support from ECF and OPCF in Hong Kong), there was significant concern that we would simply not have enough data to make informed conservation decisions. We thought about a variety of different ways to get information but one source which I had not thought of was local ecological knowledge. Basically, there are fish farmers and local residents that live in the same environment as the Eurasian otter. So maybe they can provide some ideas?

Turns out, despite very limited anecdotes about their distribution and ecology from ecologists, fish farmers and residents in the area know a lot about the species! Over 40% of the 211 people interviewed in the study reported positive records of otters. In addition to important details about the population's decline and distribution (both historical and contemporary), the local ecological knowledge also provided insights into how to conserve the species in the face of diverse threats in this rapidly urbanizing landscape.

See paper in Conservation Science & Practice

Is there a limit to how many alien bird species can establish in cities?

Toby Tsang and I began thinking about urbanization impacts on global ecological communities early on in his PhD. Toby quickly zeroed in on alien species and we wondered how urban communities might respond to introductions. We looked at this question with insects in mind first but quickly realized that there simply wasn't enough data. So we turned to birds. Ellie Dyer also joined the effort and contributed data and interpretation regarding global bird introduction histories and alien distributions.

The results of Toby's analysis showed a lack of saturation in most urban bird communities when it came to alien species richness; the only exception to this came in the most urbanized environments (which can only host a limited number of species probably). In other words, most cities globally are likely to see increasing numbers of alien species establishing in the future assuming introductions continue. Thinking back to the theme above on multiple threats... again, one of the key messages here is the interaction between multiple threats to biodiversity, in this case land-use change and invasive species.

See paper in Ecography

Concluding thoughts…

We're looking forward to the coming year and even now have a number of fun studies nearing the end of the publication production line (hopefully!). So stay tuned. There is a lot of work to be done but the lab is poised to do our small part in securing a healthy future for tropical biodiversity. Wishing you a prosperous 2020!